Dan Rubinstein

Carleton University – Plastic pollution was already viewed as one of the most pressing environmental issues on the planet when, this spring, researchers made a pair of first-time and disturbing discoveries: tiny plastic particles were detected in both human blood and human lungs.

Microplastics—pieces of plastic smaller than five millimetres in diameter that typically come from clothing, cosmetics and other everyday products that break down over time—are a mounting health and environmental concern.

They can become airborne, slip through wastewater treatment plants and are consumed by fish and other animals, contaminating natural ecosystems and our bodies. Moreover, the pandemic dramatically increased demand for personal protective equipment and take-out food containers, leading to more single-use plastic that ends up in our oceans and landfill, exacerbating this dangerous cycle.

To help address this problem, Carleton University’s Global Water Institute, which is directed by Civil and Environmental Engineering researcher Banu Örmeci, is collaborating with industry partners to develop technologies to monitor microplastics in water, air and on the land.Banu Örmeci, Director of Carleton University’s Global Water Institute and Carleton’s Jarislowsky Chair in Water and Global Health | Carleton University“Microplastics are everywhere, but because they’re still an emerging contaminant, we have neither the methods nor the equipment to measure their concentration in the environment,” says Örmeci, who is also the Carleton’s Jarislowsky Chair in Water and Global Health.

“Take a soil sample, for example. Microplastics are so small, so the first challenge is to separate them from soil, and then we still need to quantify them. We’re basically starting from scratch.”

Monitoring these pollutants is important because in order to mitigate their impact, we need to better understand where they’re present and in what quantity.

“When you conduct any type of scientific research, you make observations and reach conclusions, which often leads to loosely framed recommendations,” says Evan Pilkington, the Global Water Institute’s operations manager. “We’re taking the next step and helping create tools for people like municipal water managers and conservation authority officials, who have to respond to microplastics.

“Our work is focused on developing solutions,” he continues. “We want to empower people and give them the information and tools they need to tackle the very real challenges they’re facing.”

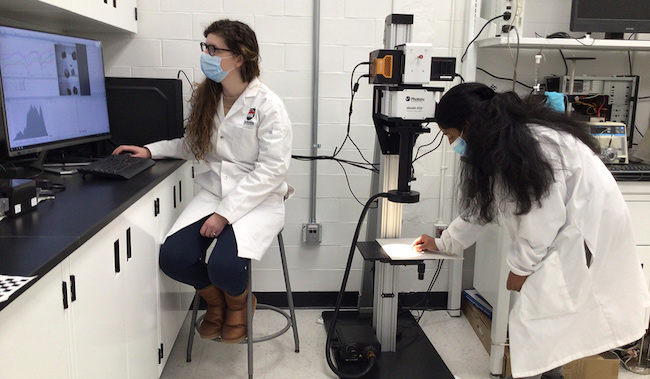

Validating and Testing New Microplastics Technologies

Funded by $250,000 grant from Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Zero Plastic Waste Funding Initiative, Global Water Institute researchers are working with a trio of companies to test and validate their technologies.

One of their partners is Montreal-based Photon etc., whose short-wave infrared hyperspectral imaging (SWIR HSI) technology supports the quick, precise and convenient analysis of microplastics in water at very low concentrations, taking this capability out of the lab and into the field. A recent experiment showed that SWIR HSI can accurately identify several microplastic polymers down to 200 microns in size. Ocean Diagnostics out of Victoria, B.C., is another partner. Instead of adapting techniques from other areas of study, researchers who study microplastics can use the company’s Saturna tool to obtain consistent sample images for rapid physical analysis of plastic particles.

Researchers who study microplastics can use the company’s Saturna tool to obtain consistent sample images for rapid physical analysis of plastic particles. | Ocean DiagnosticsSaturna uses machine learning and AI software to assess the morphology, size, shape, colour and form of a plastic particle, determining its material category— for example, whether it’s a film, a pellet or foam. Ocean Diagnostics is also developing a tool for collecting microplastic samples down to 400 metres below the surface of the ocean, which is vital because more than 99 per cent of plastic waste sinks.

The third partner is Winnipeg’s Particuleye Technologies, whose technology uses computer vision and machine learning to automate the process of counting microplastic fragments and fibres in samples, which researchers otherwise must do manually.

Although these collaborations are all relatively recent, the Global Water Institute had already acquired specific lab equipment for microplastics research, anticipating the need for more work in this area. In addition to the tech side, the institute has also been providing its partners with business and marketing advice, connecting companies to potential funders and clients.

“People and governments are very aware of plastic pollution, but they might have been more conscious of the larger pieces than the smaller pieces in the past,” says Örmeci.

“Previously, the concerns were more on the environmental side. But now there are serious questions about the impact of microplastics on human health.

“Our work is not only research,” she adds. “It’s a technology acceleration project as well, drawing on engineering, scientific and business expertise at Carleton and connecting industry, academia and government so we can develop solutions together.”